The late “Uncle Kawika” Kapahulehua, who was a member of the Papahānaumokuākea Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group (CWG), once shared about a special fishing tradition of his people, the ʻOhana Niʻihau.

Each year, eight men would journey by double-hull canoe, slicked with coconut oil and stocked with salt and supplies, across the 120 miles to Nihoa Island. Guided by southern winds and the evening stars, their intention was simple – to catch just enough fish to sustain their families. Although Kauaʻi, Niʻihau, and Nihoa are socially and politically connected as a hui moku, this journey only happened once a year for a single week in April.

CWG founding member, the late Louis “Uncle Buzzy” Agard, fished in Papahānaumokuākea back when commercial fishing was allowed. After observing the ecosystem collapsing from commercial extraction, he became a strong advocate for the protection of Papahānaumokuākea as a “Puʻuhonua no Hawaiʻi,” an ocean sanctuary. He recognized it as a breeding ground for important species that “seed” other ocean areas.

These stories from kūpuna remind us that traditional Hawaiian practices of fishing are guided by reciprocity and mutual respect; that certain areas are not open to everyone, nor are they open all the time, and to take only what is needed and to give back in return – especially in places like Papahānaumokuākea.

These stories from kūpuna remind us that traditional Hawaiian practices of fishing are guided by reciprocity and mutual respect; that certain areas are not open to everyone, nor are they open all the time, and to take only what is needed and to give back in return – especially in places like Papahānaumokuākea.

Papahānaumokuākea spans the Northwestern region of the Hawaiian Islands from Nihoa to Hōlanikū and up to 200 nautical miles from the shores of these islands, covering three-quarters of the Hawaiian archipelago and over 582,000 square miles. It is the ancestral homeland of our people, the Kānaka, and the place to which we return when we leave the physical world.

The name, Papahānaumokuākea, given by CWG elder Dr. Pualani Kanakaʻole Kanahele, is a union between two important primordial beings: Papa (Earth Mother) and Wākea (Sky Father). This union represents life, birth, growth, and regeneration.

As a puʻuhonua for millennia, a national marine monument since 2006, a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage Site since 2010, and a national marine sanctuary since early January 2025, there are strong mechanisms in place to protect Papahānaumokuākea’s natural and cultural resources, vulnerable ecosystems, and the more than 7,000 species found there.

However, just six months after its sanctuary designation, Papahānaumokuākea and our traditional Hawaiian value systems of sustainable fishing are threatened by extractive commercial fishing, economic pressures, and American politics.

The United States president, the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council (WESPAC), and their allies operate under the dangerous presumption that these are American waters and that American fishermen have the right to fish there.

On April 17, 2025, President Donald Trump signed the proclamation “Unleashing American Commercial Fishing in the Pacific,” allowing commercial fishing in parts of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument in the Central Pacific, one of the largest marine protected areas in the world.

As a result, American fishing vessels are now conducting operations in waters surrounding Kio (Wake) Island, Kalama (Johnston) Atoll, and Paukeaho (Jarvis) Island.

Shortly thereafter, Trump issued Executive Order 14276 “Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness,” directing federal agencies to slash commercial fishing regulations that protect places like Papahānaumokuākea to boost domestic production and combat foreign trade of the American seafood industry.

On June 12, 2025, WESPAC publicly reaffirmed their intention to open Papahānaumokuākea to commercial fishing and is slated to ask the president to do so.

This is not an abstract worry. It’s an immediate threat.

Prior to its prohibition, commercial fishing in Papahānaumokuākea crashed the lobster and bottom fish populations due to overextraction. The lobster decline was also linked to monk seal population declines.

And in 2000, the shark population in Papahānaumokuākea was ravaged by a single commercial fishing vessel that killed 990 manō in just 21 days.

Ironically, however, fishing prohibitions within Papahānaumokuākea actually benefit the fishing industry. Between 2014 and 2017, Hawaiian longline tuna revenue rose by 13.7% compared to 2010–2013, contradicting dire predictions of huge economic losses. Vessels can catch more fish while traveling similar distances without needing to journey into Papahānaumokuākea.

A research study published in 2022 on the “spillover effects” of marine protected areas found that ʻahi (tuna) catches increased by 54% in fishing grounds adjacent to Papahānaumokuākea. Numerous other studies affirm the importance of establishing marine protected areas as a means of boosting fish stocks and creating sustainable local fisheries outside of protected areas.

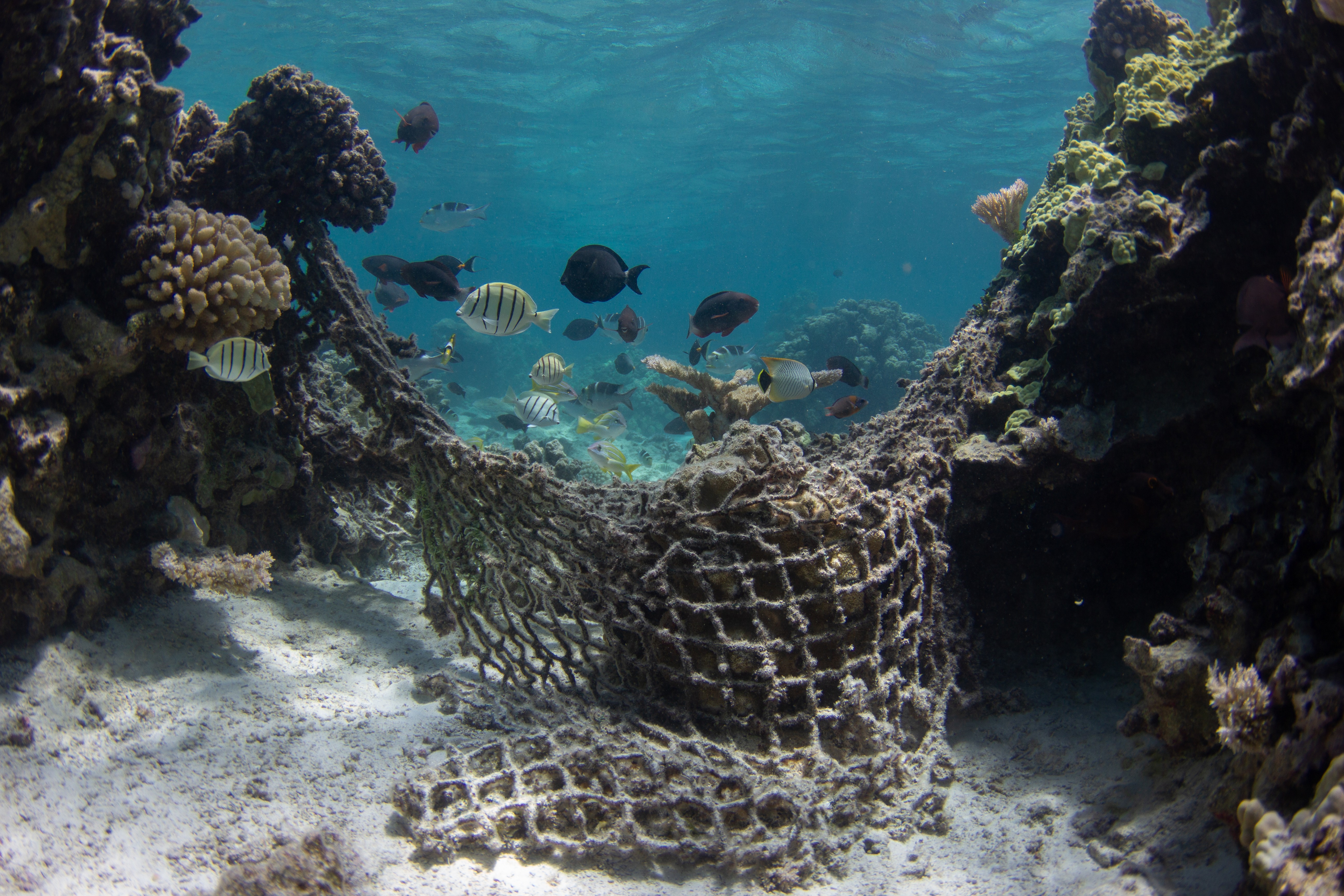

Although commercial fishing is still banned in Papahānaumokuākea, it remains vulnerable and highly impacted by the byproducts of global commercial fishing exploitation, as it has become a collection point for the world’s marine debris.

Lost fishing materials entangle corals, litter habitats, and choke wildlife. Since 2020, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Program has removed over one million pounds of marine debris from Papahānaumokuākea, much of it fishing-related. The clean-up continues.

For over 20 years, grounded in a deep living pilina of genealogy, cultural protocol, research, and stewardship, the CWG has been the most active Native Hawaiian group working to protect Papahānaumokuākea. Both the CWG and co-trustee the Office of Hawaiian Affairs staunchly oppose commercial fishing in Papahānaumokuākea.

One of the core goals of Papahānaumokuākea’s management plan is to maintain ecosystem integrity – but that goal cannot be met if commercial fishing targets key species for profit.

As Uncle Kawika always reminded us, “Inā mālama ʻoe i ke kai, mālama nō ke kai iā ʻoe. Inā mālama ʻoe i ka ʻāina, mālama nō ka ʻāina iā oe.” (If you care for the ocean, the ocean will care for you. If you care for the land, the land will care for you.)

However, a time is coming when our actions must extend beyond mālama; we must kiaʻi.

CWG member and founding NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Papahānaumokuākea superintendent ʻAulani Wilhem recalled that when CWG first began this work, “People would ask, ‘What are you protecting it from?’ And our answer was, ʻThat’s the wrong question. It’s about who and what are we protecting it for.”

Join us as we stand united in upholding Papahānaumokuākea as a puʻuhonua, a sacred refuge worthy of protection.

To learn more and stay updated on this critical issue, follow the Papahānaumokuākea Cultural Working Group on Facebook and Instagram, and visit their website: www.alohacwg.com. To express your opposition to extractive commercial fishing in Papahānaumokuākea, the CWG suggests sending letters to Hawaiʻi’s congressional representatives, to the Sanctuary Advisory Commission, and to WESPAC Executive Director Kitty Simonds, U.S. Department of Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, and Department of the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum.